Punjab State Board PSEB 6th Class Punjabi Book Solutions Chapter 5 ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ Textbook Exercise Questions and Answers.

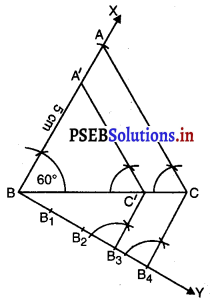

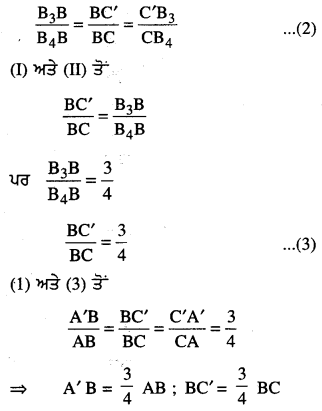

PSEB Solutions for Class 6 Punjabi Chapter 5 ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ (1st Language)

Punjabi Guide for Class 6 PSEB ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ Textbook Questions and Answers

ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ ਪਾਠ-ਅਭਿਆਸ

1. ਦੱਸ :

(ੳ) ਬੱਚੇ ਸਕੂਲ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਹਰ ਕੀ ਕਰਨ ਗਏ ਸਨ?

ਉੱਤਰ :

ਬੱਚੇ ਸਕੂਲ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਹਰ ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਦੇ ਕਹਿਣ ਅਨੁਸਾਰ ਪਿੰਡ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਇਕੱਠੇ ਕਰਨ ਗਏ ਸਨ।

(ਆ) ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ ਕਿਵੇਂ ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦੇ ਹਨ?

ਉੱਤਰ :

ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਨਾ ਗ਼ਲਦੇ ਹਨ ਤੇ ਨਾ ਸੜਦੇ ਹਨ ਤੇ ਇਧਰ-ਉਧਰ ਉੱਡਦੇ ਰਹਿੰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਇਸ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਇਹ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦੇ ਹਨ।

![]()

(ਏ) ਘਰ ਦਾ ਕੂੜਾ-ਕਰਕਟ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਪਾ ਕੇ ਬਾਹਰ ਕਿਉਂ ਨਹੀਂ ਸੁੱਟਣਾ ਚਾਹੀਦਾ?

ਉੱਤਰ :

ਕਈ ਵਾਰ ਵਿਚ ਪਾ ਕੇ ਸੁੱਟੇ ਘਰ ਦੇ ਕੂੜੇ ਵਿਚ ਕੱਚ, ਬਲੇਡ, ਪਿੰਨਾਂ ਤੇ ਸੂਈਆਂ ਹੁੰਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ। ਭੋਜਨ ਦੀ ਭਾਲ ਵਿਚ ਘੁੰਮ ਰਹੇ ਪਸ਼ੂ ਕਈ ਵਾਰ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਖਾ ਕੇ ਮੌਤ ਦੇ ਮੂੰਹ ਵਿਚ ਜਾ ਪੈਂਦੇ ਹਨ।

(ਸ) ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਵਰਤੋਂ ਬਾਰੇ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਕੀ ਕਰ ਰਹੀ ਹੈ?

ਉੱਤਰ :

ਸਰਕਾਰ ਨੇ ਕਈ ਥਾਈਂ ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਵਰਤੋਂ ਕਾਨੂੰਨੀ ਤੌਰ ‘ਤੇ ਬੰਦ ਕਰ ਦਿੱਤੀ ਹੈ ਤੇ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਰੋਕਥਾਮ ਲਈ ਕਈ ਹੋਰ ਕਦਮ ਵੀ ਚੁੱਕ ਰਹੀ ਹੈ।

(ਹ) ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਬੋਰੀਆਂ ਲਿਆ ਰਹੇ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਦੇਖ ਕੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਕਾਹਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਨੇ ਕੀ ਕਿਹਾ?

ਉੱਤਰ :

ਬਾਬਾ ਕਾਹਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਨੇ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਕਿਹਾ, “ਸ਼ਾਬਾਸ਼ ਮੁੰਡਿਓ ! ਆਹ ਤਾਂ ਬੜੀ ਵੱਡੀ ਮੱਲ ਮਾਰੀ ਹੈ। ਇਹ ਕਹਿ ਕੇ ਉਸ ਨੇ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਦੇ ਸਿਰ ਉੱਤੇ ਪਿਆਰ ਦਿੱਤਾ।

(ਕ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਜਾਂ ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ ਹੋਰ ਕਿਹੜੀ ਥਾਂ ’ਤੇ ਨੁਕਸਾਨ ਪਹੁੰਚਾਉਂਦੇ ਹਨ?

ਉੱਤਰ :

ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਜਾਂ ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਮਿੱਟੀ ਦੀ ਉਪਜਾਊ ਸ਼ਕਤੀ ਨੂੰ ਨੁਕਸਾਨ ਪਹੁੰਚਾਉਂਦੇ ਹਨ ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਇਹ ਛੇਤੀ ਗਲਦੇ ਨਹੀਂ। ਪਾਣੀ ਵਿਚ ਸੁੱਟਣ ਨਾਲ ਇਹ ਮੱਛੀਆਂ ਤੇ ਹੋਰ ਜੀਵਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਵੀ ਨੁਕਸਾਨ ਪਹੁੰਚਾਉਂਦੇ ਹਨ।

2. ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖੇ ਸ਼ਬਦਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਵਾਕਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਵਰਤੋ :

ਸਕੂਲ, ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ, ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ, ਖ਼ਤਰਨਾਕ, ਬੈਚੇਨ, ਹਿੰਮਤ

ਉੱਤਰ :

- ਸਕੂਲ ਪਾਠਸ਼ਾਲਾ)-ਬੱਚੇ ਸਕੂਲ ਵਿਚ ਪੜ੍ਹ ਰਹੇ ਹਨ।

- ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ (ਸਾਡਾ ਆਲਾ-ਦੁਆਲਾ)-ਗੱਡੀਆਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਨਿਕਲਦਾ ਧੂੰਆਂ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਵਿਚਲੀ ਹਵਾ ਨੂੰ ਬੁਰੀ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਗੰਦਾ ਕਰਦਾ ਹੈ।

- ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ)-ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ ਖ਼ਰਾਬ ਕਰ ਰਹੇ ਹਨ।

- ਖ਼ਤਰਨਾਕ ਨੁਕਸਾਨ ਦੇਣ ਵਾਲਾ)-ਸੜਕ ਉੱਤੇ ਆਵਾਜਾਈ ਦੇ ਨਿਯਮਾਂ ਦੀ ਪਾਲਣਾ ਨਾ ਕਰਨਾ ਬਹੁਤ ਖ਼ਤਰਨਾਕ ਹੈ।

- ਬੇਚੈਨ ਚੈਨ ਨਾ ਰਹਿਣਾ)-ਮਾਂ ਆਪਣੇ ਬੱਚੇ ਦੇ ਵਿਛੋੜੇ ਵਿਚ ਬੇਚੈਨ ਹੈ। 6. ਹਿੰਮਤ ਹੌਸਲਾ-ਮੁਸੀਬਤ ਦਾ ਟਾਕਰਾ ਹਿੰਮਤ ਨਾਲ ਕਰੋ !

- ਸਪੂਤ (ਚੰਗਾ ਪੁੱਤਰ)-ਸ਼ਹੀਦ ਭਗਤ ਸਿੰਘ ਭਾਰਤ ਮਾਤਾ ਦਾ ਸੱਚਾ ਸਪੂਤ ਸੀ।

- ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ (ਗੰਦਾ)-ਮੋਟਰਾਂ-ਕਾਰਾਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਨਿਕਲਦਾ ਧੂੰਆਂ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ ਬੁਰੀ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦਾ ਹੈ।

- ਡੰਗਰ ਪਸ਼)-ਡੰਗਰੇ ਖੇਤਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਚੁਗ ਰਹੇ ਹਨ।

- ਜ਼ਹਿਰੀਲੇ (ਜ਼ਹਿਰ ਭਰੇ)-ਕਈ ਸੱਪ ਬਹੁਤ ਜ਼ਹਿਰੀਲੇ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ !

- ਹਾਨੀਕਾਰਕ ਨੁਕਸਾਨਦੇਹ)-ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਪ੍ਰਦੂਸ਼ਣ ਮਨੁੱਖੀ ਸਿਹਤ ਲਈ ਬਹੁਤ ਹਾਨੀਕਾਰਕ ਹੈ।

- ਪਦਾਰਥ (ਚੀਜ਼ਾਂ, ਵਸਤਾਂ)-ਪ੍ਰਦੂਸ਼ਣ ਕਾਰਨ ਧਰਤੀ ਦੇ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਵਿਚ ਬਹੁਤ ਸਾਰੇ ਜ਼ਹਿਰੀਲੇ ਪਦਾਰਥ ਮਿਲ ਗਏ ਹਨ।

- ਉਪਜਾਊ ਪੈਦਾ ਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਤਾਕਤ)-ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਜ਼ਮੀਨ ਬੜੀ ਉਪਜਾਊ ਹੈ।

- ਸੈਰ-ਸਪਾਟਾ (ਘੁੰਮਣਾ, ਫਿਰਨਾ)-ਅਸੀਂ ਕਸ਼ਮੀਰ ਵਿਚ ਸੈਰ-ਸਪਾਟਾ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਗਏ।

- ਮੱਲ ਮਾਰਨੀ ਵੱਡੀ ਪ੍ਰਾਪਤੀ ਕਰਨੀ)-ਦਸਵੀਂ ਵਿਚ 40% ਨੰਬਰ ਲੈ ਕੇ ਤੂੰ ਕੋਈ ਵੱਡੀ ਮੱਲ ਨਹੀਂ ਮਾਰੀ।

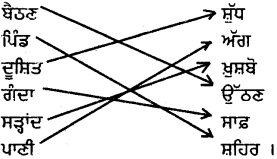

![]()

3. ਔਖੇ ਸ਼ਬਦਾਂ ਦੇ ਅਰਥ :

- ਸਪੂਤ : ਚੰਗਾ ਪੁੱਤਰ, ਆਗਿਆਕਾਰ ਪੁੱਤਰ

- ਸ਼ਕਤੀ : ਤਾਕਤ

- ਹਾਨੀਕਾਰਕ : ਨੁਕਸਾਨਦੇਹ, ਨੁਕਸਾਨਦਾਇਕ

- ਉਪਜਾਊ : ਜਿਸ ਥਾਂ ਪੈਦਾਵਾਰ ਬਹੁਤ ਹੋਵੇ।

4. ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖੇ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਕਿਸ ਨੇ, ਕਿਸ ਨੂੰ ਕਹੇ :

(ੳ) “ਕਿਉਂ ਐਵੇਂ ਸ਼ੂਕਦਾ ਪਿਆ ਏ? ਆਹ ਤੇਰੀ ਉਮਰ ਏ ਐਵੇਂ ਨਿਆਣਿਆਂ ਦੇ ਮਗਰ ਭੱਜਣ ਦੀ?

(ਅ) ਸ਼ੈਤਾਨ! ਇੱਕ ਵਾਰੀ ਮੇਰੇ ਹੱਥ ਆ ਜਾਓ ਸਹੀ, ਗਿੱਟੇ ਨਾ ਸੇਕ ਦਿਆਂ ਤਾਂ।”

(ਏ) ਪਰ ਅੱਗ ਲਾਉਣੀ ਵੀ ਤਾਂ ਖ਼ਤਰਨਾਕ ਹੈ ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਪੌਲੀਥੀਨ ਅੰਦਰ ਜ਼ਹਿਰੀਲੇ ਪਦਾਰਥ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ੳ) ਬੇਬੇ ਕਰਤਾਰੀ ਨੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਕਾਹਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਨੂੰ ਕਹੇ।

(ਅ) ਬਾਬਾ ਕਾਹਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਨੇ ਪੋਤਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਕਹੇ।

(ਈ) ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਕਾਹਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਨੂੰ ਕਹੇ।

5. ਖਾਲੀ ਥਾਵਾਂ ਭਰੋ :

(ੳ) …………………… ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ ਸਾਰੇ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦੇ ਹਨ।

(ਅ) ਪੌਲੀਥੀਨ ਅੰਦਰ …………………… ਪਦਾਰਥ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਹਨ।

(ਏ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਮਿੱਟੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਦੱਬਣ ਨਾਲ ਜ਼ਮੀਨ ਦੀ …………………… ਘੱਟ ਜਾਵੇਗੀ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ੳ) ਗਿਲੀਆਂ,

(ਅ) ਉਪਜਾਊ ਸ਼ਕਤੀ, ਈ ਜ਼ਹਿਰੀਲੇ,

(ਸ) ਅਫ਼ਸੋਸ।

ਵਿਆਕਰਨ :

ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖੇ ਸ਼ਬਦਾਂ ਕਿਹੜੀ ਪ੍ਰਕਾਰ ਦੇ ਨਾਂਵ ਹਨ :

ਪਿੰਡ, ਸਕੂਲ, ਮਨਜੀਤ, ਸੰਤੋਖ, ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ, ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ, ਕੂੜਾ-ਕਰਕਟ, ਸਰਕਾਰ, ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਉ) ਪਿੰਡ, ਸਕੂਲ, ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ, ਸਰਕਾਰ, ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ-ਆਮ ਨਾਂਵ।

(ਅ) ਮਨਜੀਤ, ਸੰਤੋਖ਼-ਖ਼ਾਸ ਨਾਂਵ

(ਈ) ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ, ਕੂੜਾ-ਕਰਕਟ-ਵਸਤਵਾਚਕ ਨਾਂਵ।

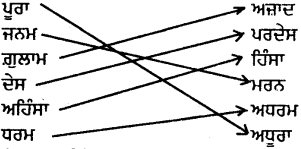

![]()

ਅਧਿਆਪਕ ਲਈ :

ਵਿਦਿਆਰਥੀਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ ਅਤੇ ਪ੍ਰਦੂਸ਼ਣ ਫੈਲਾਉਣ ਵਾਲੀ ਹੋਰ ਸਮਗਰੀ ਦਾ ਨਿਪਟਾਰਾ ਕਰਨ ਸੰਬੰਧੀ ਢੁਕਵੀਂ ਜਾਣਕਾਰੀ ਪ੍ਰਦਾਨ ਕਰੋ।

PSEB 6th Class Punjabi Guide ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ Important Questions and Answers

ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ- “ਪਾਠ ਦਾ ਸਾਰ ਲਿਖੋ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

ਗੁਰਦੀਪ, ਮਨਜੀਤ ਤੇ ਸੰਤੋਖ ਚੀਕਾਂ ਮਾਰਦੇ ਸਕੂਲ ਨੂੰ ਨੱਠੇ ਜਾ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ। ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੇ ਮਗਰ ਡਾਂਗਾਂ ਚੁੱਕੀ ਦੌੜਦੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਕਾਹਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਨੂੰ ਸਾਹ ਚੜ੍ਹ ਗਿਆ ਸੀ ਤੇ ਉਹ ਰੁਕ ਕੇ ਉੱਚੀ-ਉੱਚੀ ਬੋਲਦਾ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਰੁੱਧ ਆਪਣਾ ਗੁੱਸਾ ਜ਼ਾਹਰ ਕਰ ਰਿਹਾ ਸੀ। ਬੇਬੇ ਕਰਤਾਰੀ ਦੇ ਪੁੱਛਣ ‘ਤੇ ਉਸਨੇ ਦੱਸਿਆ ਕਿ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਘਰੋਂ ਤਾਂ ਸਕੂਲੇ ਭੇਜਿਆ ਸੀ, ਪਰ ਪਤਾ ਨਹੀਂ, ਇਹ ਕਿਉਂ ਗਲੀਆਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਖੇਹ-ਸੁਆਹ ਚੁਗ ਰਹੇ ਹਨ।

ਉਹ ਕਰਤਾਰੀ ਦੇ ਕਹਿਣ ‘ਤੇ ਨਾ ਰੁਕਿਆ ਤੇ ਡਾਂਗ ਖੜਕਾਉਂਦਾ ਪੋਤਿਆਂ ਦੇ ਮਗਰ ਸਕੂਲ ਜਾ ਪੁੱਜਾ ਤੇ ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਕਹਿਣ ਲੱਗਾ ਕਿ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੇ ਘਰੋਂ ਤਾਂ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਸਕੂਲ ਭੇਜਿਆ, ਪਰ ਇਹ ਬਾਹਰ ਕੀ ਕਰਦੇ ਫਿਰਦੇ ਹਨ !

ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਕੁਰਸੀ ਉੱਤੇ ਬਿਠਾ ਕੇ ਦੱਸਿਆ ਕਿ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੇ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਡਿਊਟੀ ਲਾਈ ਸੀ ਕਿ ਉਹ ਇਕ ਘੰਟਾ ਪਿੰਡ ਦੀ ਸਫ਼ਾਈ ਕਰਨ। ਬਾਬੇ ਨੇ ਕਿਹਾ ਕਿ ਉਹ ਤਾਂ ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਇਕੱਠੇ ਕਰ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ। ਇਸ ਦੀ ਕੀ ਲੋੜ ਸੀ?

ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਦੱਸਿਆ ਕਿ ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਸਾਰੇ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ ਦੁਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਇਹ ਨਾ ਗ਼ਲਦੇ ਹਨ ਤੇ ਨਾ ਸੜਦੇ ਹਨ, ਸਗੋਂ ਉੱਡ ਕੇ ਨਾਲੀਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਫਸ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ ਤੇ ਪਾਣੀ ਨੂੰ ਰੋਕ ਦਿੰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਇਸ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਰੁਕਿਆ ਪਾਣੀ ਸੜਾਂਦ ਮਾਰਨ ਲੱਗ ਪੈਂਦਾ ਹੈ। ਇਸ ਸਮੇਂ ਬਾਬੇ ਨੂੰ ਵੀ ਚੇਤਾ ਆ ਗਿਆ ਕਿ ਇਕ ਦਿਨ ਉਸ ਦੇ ਆਪਣੇ ਖੇਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਪਾਣੀ ਖ਼ਾਲ ਵਿਚ ਫਸੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਕਾਰਨ ਹੀ ਹੁਕਿਆ ਹੋਇਆ ਸੀ !

ਬਾਬੇ ਦੇ ਵੱਡੇ ਪੋਤੇ ਗੁਰਦੀਪ ਨੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਦੱਸਿਆ ਕਿ ਕਈ ਵਾਰੀ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ, ਜਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਲੋਕੀਂ ਕੂੜਾ-ਕਰਕਟ, ਬਲੇਡ, ਸੂਈਆਂ ਤੇ ਪਿੰਨਾਂ ਬੰਦ ਕਰ ਕੇ ਬਾਹਰ ਸੁੱਟ ਦਿੰਦੇ ਹਨ, ਡੰਗਰ ਖਾ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ ਤੇ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਤਿੱਖੀਆਂ ਚੀਜ਼ਾਂ ਨਾਲ ਭੋਜਨ ਨਲੀ ਵਿਚ ਜ਼ਖ਼ਮ ਹੋਣ ਕਰਕੇ ਜਾਂ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੇ ਫਸਣ ਕਰਕੇ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਮੌਤ ਹੋ ਸਕਦੀ ਹੈ ਇਹ ਸੁਣ ਕੇ ਬਾਬੇ ਨੇ ਕਿਹਾ ਕਿ ਜੇਕਰ ਇਹ ਗੱਲ ਹੈ, ਤਾਂ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਅੱਗ ਲਾ ਦੇਣੀ ਚਾਹੀਦੀ ਹੈ।

ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਦੱਸਿਆ ਕਿ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਅੱਗ ਲਾਉਣੀ ਵੀ ਖ਼ਤਰਨਾਕ ਹੈ। ਇਸ ਨਾਲ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਬਹੁਤ ਹੀ ਜ਼ਹਿਰੀਲੀਆਂ ਗੈਸਾਂ ਨਿਕਲਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ, ਜੋ ਸਿਹਤ ਲਈ ਹਾਨੀਕਾਰਕ ਹੁੰਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ।

![]()

ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਹੋਰ ਦੱਸਿਆ ਕਿ ਇਹ ਜ਼ਮੀਨ ਵਿਚ ਦੱਬਣ ਨਾਲ ਜ਼ਮੀਨ ਦੀ ਉਪਜਾਊ ਸ਼ਕਤੀ ਘਟ ਜਾਂਦੀ ਹੈ। ਜੇਕਰ ਇਸ ਨੂੰ ਵਗਦੇ ਪਾਣੀ ਵਿਚ ਸੁੱਟੀਏ, ਤਾਂ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਨਿਗਲ ਕੇ ਮੱਛੀਆਂ ਮਰ ਜਾਂਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ। ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਦੇ ਪੁੱਛਣ ਤੇ ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਦੱਸਿਆ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਤੋਂ ਛੁਟਕਾਰੇ ਦਾ ਹੱਲ ਇਹੋ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਵਰਤੋਂ ਹੀ ਬੰਦ ਕਰ ਦਿੱਤੀ ਜਾਵੇ ! ਸਰਕਾਰ ਨੇ ਕਈ ਥਾਂਵਾਂ, ਖ਼ਾਸ ਕਰਕੇ ਸੈਰ-ਸਪਾਟੇ ਦੀਆਂ ਥਾਂਵਾਂ ਉੱਤੇ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਵਰਤੋਂ ਉੱਤੇ ਪਾਬੰਦੀ ਲਾ ਦਿੱਤੀ ਹੈ, ਜਿਵੇਂ ਹਿਮਾਚਲ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਨੇ ਕੀਤਾ ਹੈ।

ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਦੀਆਂ ਗੱਲਾਂ ਸੁਣ ਕੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਕਿਹਾ ਕਿ ਫਿਰ ਤਾਂ ਉਸ ਦੇ ਪੋਤੇ ਨੇ ਬੜਾ ਚੰਗਾ ਕੀਤਾ ਹੈ। ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਆਪਣੇ ਗੁੱਸੇ ਉੱਤੇ ਦੁੱਖ ਪ੍ਰਗਟ ਕੀਤਾ। ਇੰਨੇ ਨੂੰ ਕੁੱਝ ਹੋਰ ਬੱਚੇ ਮੋਮੀ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਭਰੀਆਂ ਬੋਰੀਆਂ ਘਸੀਟਦੇ ਲਿਆ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਸਭ ਨੂੰ ਸ਼ਾਬਾਸ਼ ਦਿੱਤੀ ਤੇ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੇ ਸਿਰ ਉੱਤੇ ਹੱਥ ਫੇਰਦੇ ਉਹ ਖੇਤਾਂ ਵਲ ਤੁਰ ਪਏ।

ਔਖੇ ਸ਼ਬਦਾਂ ਦੇ ਅਰਥ-ਸ਼ੋਰ – ਰੌਲਾ ਸ਼ੈਤਾਨੋ – ਸ਼ੈਤਾਨੀ ਕਰਨ ਵਾਲਿਓ। ਗਿੱਟੇ ਨਾ ਸੇਕ ਦਿਆਂ – ਬੁਰੀ ਕੁਟਾਂਗਾ। ਸ਼ੁਕਦਾ ਪਿਆ ਏ – ਗੁੱਸੇ ਨਾਲ ਬੋਲਦਾ ਪਿਆ ਹੈਂ। ਭੱਜਣ – ਦੌੜਨ ਸਪੂਤਾਂ – ਭਾਵ ਚੰਗੇ ਪੁੱਤਰਾਂ ਕੱਚੀ ਬੁੱਧ – ਬੱਚੇ ਦੀ ਸਮਝ, ਘੱਟ ਸੂਝ-ਸਮਝ ਸਟਾਫ਼ ਰੂਮ – ਅਧਿਆਪਕਾਂ ਦੇ ਬੈਠਣ ਦੀ ਥਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਚੈੱਕ ਕਰ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ – ਚੰਗੀ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੇਖ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ। ਡਿਉਟੀ – ਜ਼ਿੰਮੇਵਾਰੀ। ਮੋਮਜਾਮਾ – ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ – ਸਾਡਾ ਆਲਾ-ਦੁਆਲਾ ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ – ਗੰਦਾ ਸੜਾਂਦ – ਬਦਬੋ। ਡੰਗਰ – ਪਸ਼ੂ। ਤਲਾਸ਼ – ਖੋਜ ਕਰਨਾ, ਲੱਭਣਾ। ਭੋਜਨ ਨਲੀ – ਭੋਜਨ ਦੇ ਮੁੰਹ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਢਿੱਡ ਤਕ ਜਾਣ ਦਾ ਰਸਤਾ ! ਅਟਕ – ਰੁਕ। ਪੋਲੀਥੀਨ – ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਪਦਾਰਥ – ਚੀਜ਼ਾਂ ਹਾਨੀਕਾਰਕ – ਨੁਕਸਾਨ ਦੇਣ ਵਾਲਾ ਉਪਜਾਊ ਸ਼ਕਤੀ – ਪੈਦਾ ਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਤਾਕਤ। ਸੈਰ-ਸਪਾਟਾ – ਸੈਰ ਕਰਨਾ, ਘੁੰਮਣਾ-ਫਿਰਨਾ ਝਲਕ-ਚਮਕ ਮਲ਼ ਮਾਰੀ ਐ – ਕੋਈ ਵੱਡੀ ਚੀਜ਼ ਪ੍ਰਾਪਤ ਕੀਤੀ ਹੈ।

1. ਵਿਆਕਰਨ

ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ 1.

ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖੇ ਵਾਕਾਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਨਾਂਵ ਚੁਣੋ ਤੇ ਉਨਾਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਕਿਸਮਾਂ ਦੱਸੋ

(ਉ) ਪਿੰਡ ਦੀਆਂ ਗਲੀਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਸ਼ੋਰ ਪਿਆ ਹੋਇਆ ਹੈ

(ਅ) ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਸਟਾਫ਼-ਰੂਮ ਵਿਚ ਬੈਠੇ ਕਾਪੀਆਂ ਚੈੱਕ ਕਰ ਰਹੇ ਹਨ

(ਈ) ਉਹਨਾਂ ਦੇ ਪੋਤਿਆਂ ਦੇ ਚਿਹਰਿਆਂ ਉੱਤੇ ਮੁਸਕਰਾਹਟ ਝਲਕ ਰਹੀ ਸੀ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਉ) ਪਿੰਡ, ਗਲੀਆਂ- ਆਮ ਨਾਂਵ।

ਸ਼ੋਰ-ਭਾਵਵਾਚਕ ਨਾਂਵ।

(ਅ) ਮਾਸਟਰ, ਕਾਪੀਆਂ-ਆਮ ਨਾਂਵ।

ਸਟਾਫ਼-ਰੂਮ-ਖ਼ਾਸ ਨਾਂਵ।

(ਈ) ਪੋਤਿਆਂ, ਚਿਹਰਿਆਂ-ਆਮ ਨਾਂਵ !

ਮੁਸਕਰਾਹਟ-ਭਾਵਵਾਚਕ ਨਾਂਵ।

![]()

2. ਪੈਰਿਆਂ ਸੰਬੰਧੀ ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ

ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ 1.

ਹੇਠ ਦਿੱਤੇ ਪੈਰੇ ਨੂੰ ਪੜ੍ਹੋ ਅਤੇ ਦਿੱਤੇ ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨਾਂ ਦੇ ਬਹੁਵਿਕਲਪੀ ਉੱਤਰਾਂ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਸਹੀ ਉੱਤਰ ਚੁਣੋ :

ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਬੈਠਣ ਲਈ ਕੁਰਸੀ ਦਿੱਤੀ ਅਤੇ ਕਿਹਾ … “ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ, ਇਹਨਾਂ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਪਿੰਡ ਦੇ ਆਲੇ-ਦੁਆਲੇ ਨੂੰ ਸਾਫ਼ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਭੇਜਿਆ ਸੀ। ਇਹਨਾਂ ਦੀ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਹੋਰ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਵੀ ਇੱਕ ਘੰਟੇ ਲਈ ਡਿਊਟੀ ਲਾਈ ਗਈ ਏ।” ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਬੋਲੇ, ‘‘ਪਰ ਇਹ ਤਾਂ ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਇਕੱਠੇ ਕਰਦੇ ਸੀ। ਭਲਾ ਇਹਦੀ ਕੀ ਲੋੜ, ਤਾਂ ਆਪੇ ਹੀ ਹਵਾ ਵਿੱਚ ਇੱਧਰ-ਉੱਧਰ ਉੱਡ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਨੇ।’

ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਬੈਠਣ ਦਾ ਇਸ਼ਾਰਾ ਕੀਤਾ ਅਤੇ ਕਹਿਣ ਲੱਗੇ, ‘‘ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ, ਤੁਹਾਨੂੰ ਤਾਂ ਪਤੈ.. ਇਹ ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਸਾਰੇ ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਇਹ ਨਾ ਗਲਦੇ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਨਾ ਹੀ ਸੜਦੇ ਹਨ। ਉੱਡ ਕੇ ਇਹ ਨਾਲੀਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਚਲੇ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਪਾਣੀ ਦਾ ਰਸਤਾ ਰੋਕ ਦਿੰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਨਾਲੀਆਂ ਦਾ ਗੰਦਾ ਪਾਣੀ ਗਲੀਆਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਇਕੱਠਾ ਹੋ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਫਿਰ ਸਭ ਪਾਸੇ ਸੜਾਂਦ ਮਾਰਦਾ ਹੈ।” ‘‘ਓ-ਹੋ, ਹੁਣ ਸਮਝ ਆਈ ਕਿ ਪਿੰਡ ਦੀਆਂ ਨਾਲੀਆਂ ਬੰਦ ਕਿਉਂ ਰਹਿੰਦੀਆਂ ਨੇ?”

ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਸਿਰ ਹਿਲਾਉਂਦੇ ਹੋਏ ਆਖਿਆ। ਫਿਰ ਮੱਥੇ ‘ਤੇ ਹੱਥ ਫੇਰਦੇ ਹੋਏ ਉਹ ਥੋੜੀ ਦੇਰ ਰੁਕ ਕੇ ਬੋਲੇ … ‘‘ਹਾਂ ਚੇਤੇ ਆਈ ਗੱਲ ਉਸ ਦਿਨ ਮੈਂ ਖੇਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਪਾਣੀ ਲਾ ਰਿਹਾ ਸਾਂ …. ਪਾਣੀ ਤਾਂ ਕੀੜੀ ਦੀ ਚਾਲ ਤੁਰਿਆ ਆ ਰਿਹਾ ਸੀ। ਵੇਖਿਆ ਤਾਂ ਖਾਲ ਵਿਚ ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ ਫਸੇ ਪਏ ਸਨ। ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫੇ ਬਾਹਰ ਕੱਢੇ ਤਾਂ ਜਾ ਕੇ ਖੇਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਪਾਣੀ ਤੁਰਿਆ।’’ ‘‘ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ, ਇਹ ਖਾ ਕੇ ਕਈ ਡੰਗਰ ਵੀ ਮਰ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਨੇ”, ਗੁਰਦੀਪ ਬੋਲਿਆ

1. ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਨੂੰ ਬੈਠਣ ਲਈ ਕੀ ਦਿੱਤਾ?

(ਉ ਮੋਮਜਾਮਾ.

(ਅ) ਕੁਰਸੀ

(ਇ) ਟਾਟ

(ਸ) ਮੰਜਾ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਅ) ਕੁਰਸੀ

2. ਬੱਚਿਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਪਿੰਡ ਵਿਚ ਕੀ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਭੇਜਿਆ ਗਿਆ ਸੀ?

(ਉ) ਪੜ੍ਹਾਈ

(ਅ) ਸਫ਼ਾਈ

(ਏ) ਵਾਢੀ

(ਸ) ਉਗਰਾਹੀ

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਅ) ਸਫ਼ਾਈ

3. ਬੱਚੇ ਪਿੰਡ ਵਿਚ ਕਿਹੜੇ ਇਕੱਠੇ ਕਰ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ?

(ੳ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ/ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ

(ਅ) ਕਾਗ਼ਜ਼ ਦੇ

(ਇ) ਕੱਪੜੇ ਦੇ

(ਸ) ਗੱਤੇ ਦੇ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ੳ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ/ਮੋਮਜਾਮੇ ਦੇ

![]()

4. ਹਵਾ ਨਾਲ ਕਿਧਰ ਉੱਡ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ?

(ਉ) ਅਸਮਾਨ ਵਲ

(ਅ) ਘਰਾਂ ਵਲ

(ਈ) ਢੇਰਾਂ ਵਲ

(ਸ) ਇੱਧਰ-ਉੱਧਰ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਸ) ਇੱਧਰ-ਉੱਧਰ।

5. ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਕਿਸ ਨੂੰ ਦੂਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦੇ ਹਨ?

(ਉ) ਹਵਾ ਨੂੰ

(ਅ) ਪਾਣੀ ਨੂੰ

(ੲ) ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ

(ਸ) ਭੋਜਨ ਨੂੰ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ੲ) ਵਾਤਾਵਰਨ ਨੂੰ

6. ਕਿਸ ਚੀਜ਼ ਦੇ ਫਸਣ ਨਾਲ ਨਾਲੀਆਂ ਰੁੱਕ ਜਾਂਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ?

(ਉ) ਕੱਖ-ਕਾਨ

(ਅ) ਘਾਹ-ਫੂਸ

(ਇ) ਮਲਬਾ

(ਸ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਸ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ।

7. ਇਕ ਦਿਨ ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ ਖੇਤਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਕੀ ਕਰ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ?

(ਉ ਵਾਢੀ।

(ਅ) ਬਿਜਾਈ

(ਇ) ਗੁਡਾਈ

(ਸ) ਸਿੰਚਾਈ/ਪਾਣੀ ਲਾ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਸ) ਸਿੰਚਾਈ/ਪਾਣੀ ਲਾ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ।

![]()

8. ਨਾਲੀਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਇਕੱਠਾ ਹੋਇਆ ਕਿਹੜਾ ਪਾਣੀ ਸੜਾਂਦ ਮਾਰਦਾ ਹੈ?

(ਉ) ਸਾਫ਼

(ਅ) ਦਾ

(ਇ) ਮੀਂਹ ਦਾ।

(ਸ) ਘਰਾਂ ਦਾ !

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਇ) ਮੀਂਹ ਦਾ।

9. ਕੀ ਖਾ ਕੇ ਡੰਗਰ ਮਰ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ?

(ੳ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ

(ਅ) ਕਾਗਜ਼ ਦੇ

(ਈ) ਚਰਾਗਾਹ ਦਾ ਘਾਹ

(ਸ) ਗੁਤਾਵਾ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ੳ) ਪਲਾਸਟਿਕ ਦੇ

10. ਕਿਸ ਨੇ ਕਿਹਾ ਸੀ ਕਿ ਖਾ ਕੇ ਕਈ ਡੰਗਰ ਵੀ ਮਰ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਹਨ?

(ਉ) ਹਰਦੀਪ ਨੇ

(ਅ) ਗੁਰਦੀਪ ਨੇ।

(ਈ) ਮਨਦੀਪ ਨੇ।

(ਸ) ਬਲਦੀਪ ਨੇ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਅ) ਗੁਰਦੀਪ ਨੇ।

ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ :

(i) ਉਪਰੋਕਤ ਪੈਰੇ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਕੋਈ ਪੰਜ ਨਾਂਵ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਚੁਣੋ।

(ii) ਉਪਰੋਕਤ ਪੈਰੇ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਕੋਈ ਪੰਜ ਪੜਨਾਂਵ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਚੁਣੋ।

(ii) ਉਪਰੋਕਤ ਪੈਰੇ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਕੋਈ ਪੰਜ ਵਿਸ਼ੇਸ਼ਣ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਚੁਣੋ।

(iv) ਉਪਰੋਕਤ ਪੈਰੇ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਕੋਈ ਪੰਜ ਕਿਰਿਆ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਚੁਣੋ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(i) ਮਾਸਟਰ ਜੀ, ਬਾਬਾ ਜੀ, ਕੁਰਸੀ, ਬੱਚਿਆਂ, ਲਿਫ਼ਾਫ਼ੇ।

(ii) ਇਹ, ਕੀ, ਆਪੇ, ਤੁਹਾਨੂੰ, ਉਹ।

(iii) ਇਕ, ਦੁਸ਼ਿਤ, ਗੰਦਾ, ਉਸ, ਕਈ।

(iv) ਦਿੱਤੀ, ਕਿਹਾ, ਭੇਜਿਆ ਸੀ, ਲਾਈ ਗਈ ਏ, ਉੱਡ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਨੇ।

![]()

ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ 3.

ਉਪਰੋਕਤ ਪੈਰੇ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖੇ ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨਾਂ ਦੇ ਸਹੀ ਉੱਤਰ ਚੁਣੋ

(i) ‘ਮਾਸਟਰ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਦਾ ਇਸਤਰੀ ਲਿੰਗ ਚੁਣੋ

(ਉ) ਮਾਸਟਰੀ

(ਅ) ਮਾਸਟਰਨੀ

(ਈ) ਮਾਸਟਰਾਣੀ।

(ਸ) ਮਾਸਟਰਾਨੀ !

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਈ) ਮਾਸਟਰਾਣੀ।

(ii) ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖਿਆਂ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਕਿਹੜਾ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਵਿਸ਼ੇਸ਼ਣ ਹੈ?

(ਉ) ਗੰਦਾ

(ਅ) ਸੜਾਂਦ

(ਇ) ਪਾਸੇ

(ਸ) ਇਸ਼ਾਰਾ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਉ) ਗੰਦਾ

(iii) ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖਿਆਂ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ‘ਡੰਗਰ ਦਾ ਸਮਾਨਾਰਥਕ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਕਿਹੜਾ ਹੈ?

(ਉ) ਮੰਦਰ

(ਅ) ਪਸ਼ੂ

(ਇ) ਡੰਰਾਣਾ

(ਸ) ਜਾਨਵਰ।

ਉੱਤਰ :

(ਅ) ਪਸ਼ੂ

ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ 4.

ਉਪਰੋਕਤ ਪੈਰੇ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਹੇਠ ਲਿਖੇ ਵਿਸਰਾਮ ਚਿੰਨ੍ਹ ਲਿਖੋ

(i) ਡੰਡੀ

(ii) ਕਾਮਾ

(iii) ਪੁੱਠੇ ਕਾਮੇ

(iv) ਜੋੜਨੀ

ਉੱਤਰ :

(i) ਡੰਡੀ ( । )

(ii) ਕਾਮਾ (,)

(ii) ਪੁੱਠੇ ਕਾਮੇ (”)

(iv) ਜੋੜਨੀ (-)

![]()

ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਨ 5.

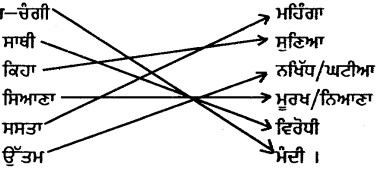

ਉਪਰੋਕਤ ਪੈਰੇ ਵਿੱਚੋਂ ਵਿਰੋਧੀ ਸ਼ਬਦਾਂ ਦਾ ਸਹੀ ਮਿਲਾਨ ਕਰੋ :

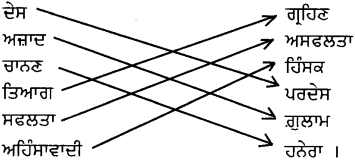

ਉੱਤਰ :